The only certainty

Ever since Boris Johnson succeeded Theresa May as the next British Prime Minister, his absolutely resolute stance on the Brexit deadline has been the only agenda of his cabinet that appears to be a solidified top priority. He insists that the UK is going to leave the European bloc by the 31st of October 2019, with or without a trade deal, and yet, regardless of how adamant he sounds in his rhetoric, Johnson still has the toughest task ahead of him – proving that he is capable of negotiating with the EU Commission, and not merely appealing to populist goals.

Johnson has inherited a divided Parliament and a weakened Tory party from May, both of which have suffered from her long-lasting struggle to secure a trade deal that satisfies all concerned parties. The biggest obstacle to achieving this, however, has been the widely disputed issue of the Irish border and the apparent reluctance by both the EU and the UK to compromise and meet the demands of each other.

On the one hand, Brexiteers want to have a hard Irish border, meaning that the UK would be less politically connected with the bloc after the official divorce, whereas on the other hand, the EU Commission has insisted on an Irish border' Backstop, which would support an easier movement of people and therefore, support the establishment of closer political ties between the two.

For Boris Johnson, the question of the Irish border is not only a stumbling block in the negotiations between the UK and the EU but also an expression of his political stoicism, exemplifying his desire to be perceived as an unwavering leader. Arguably, that is the most significant difference between him and his predecessor. While Theresa May attempted to repackage the same trade deal proposal on three different occasions, only to get her plans wholly shattered in the House of Commons, Boris Johnson is constantly attesting to his unwillingness to compromise, and that it is the EU that has to change their demands.

Essentially, Johnson is making a very risky bet, now that he tries to pressure the EU with the threat of a no-deal Brexit even though the real leverage is in the hands of the EU Commission itself since a Hard Brexit would mostly disadvantage the UK. The question is, could Boris Johnson's hardball tactic produce results?

Different Priorities

Ultimately, the chances of the two sides reaching a mutually satisfactory agreement prior to the 31st of October seem increasingly diminished, owing to the different priorities that they profess. As it was already stated, the EU Commission's top priority is to protect the integrity of the bloc's member states, and in doing so, they would defend the key values of the union, including the freedom of movement. The EU Commission seems very unlikely to back up from its current stance on the Irish border for as long as that freedom is put at risk by the Brexit ambiguity of the Eurosceptics.

Accordingly, for Boris Johnson, the underlying question has an entirely different dimension. He seems to be preoccupied with matters of political discourse more than with pursuing economic goals. He has remained true to his initial comments, continually saying that the British voters’ wishes have to be satisfied and that Brexit has to be delivered, but does that mean that he is a true champion of democracy, or does it mean that he is willing to put the future of Britain at risk by pursuing populist goals? Or could it be instead that he recognises the inescapability of the situation and is making early preparations ahead of an inevitable hard Brexit?

Johnson, the negotiator

This week marks the first time Boris Johnson travels overseas as a Prime Minister of the UK, as he is visiting Berlin on the 21st of August and Paris on the 22nd, in a bid to convince Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron, it is the EU that has to submit to his demands if they want to have a lengthy trade partnership with Britain after the 31st of October.

It appears that Johnson wants to play hardball with the top leaders in Europe, by maintaining a dispassionate image intending to show them that the UK does not fear a no-deal Brexit, and to really put the pressure on the EU Commission, however, his effort might be perceived as a last-ditch attempt to salvage something out of an unwinnable situation. His travels coincide with a recently released report by the British Government, that illustrates a grim outlook on the prospects of the British economy, should the country really crash out of the bloc on the 31st without a trade deal. The findings of the report demonstrate that there are going to be food shortages and medicine shortages at least throughout the first three months after the official departure.

It would appear that Boris Johnson is going to Berlin and then Paris knowing fully-well what is at stake for his cabinet, which it seems is hoping for the best but bracing for the worst. So, what are the chances that the EU would reconsider its initial stance and deal with Johnson? Antecedently, the biggest concern for European leaders has been the image of unity that the bloc has managed to sustain so far, and whether it is going to be shattered in case that Britain is allowed to trump over the bloc’s integrity. It is for that reason that the Irish border has become the prime highlight of many heated debates lasting for over two years now.

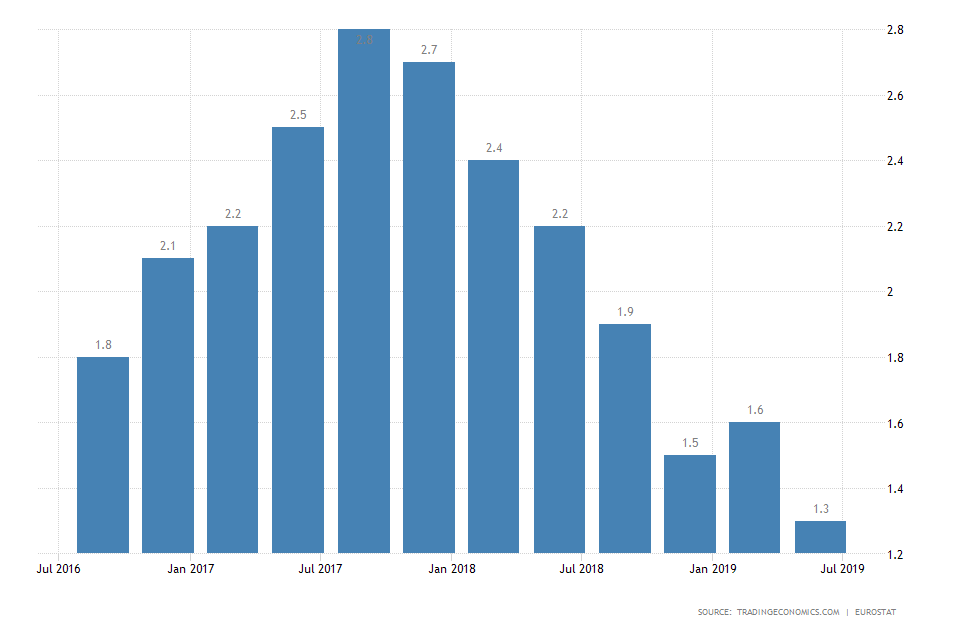

Nevertheless, the underlying circumstances have changed markedly since the Brexit vote in 2016, and the situation has acquired an entirely different scope. Now both internal and external factors might pressure the EU into rethinking its original stance. Firstly, the prospects for European GDP growth have greatly deteriorated in recent times, owing to the heightened trade uncertainty resulting from the ongoing trade war between the US and China. The annual gross domestic product of the bloc has decreased to 1.3 per cent in the second quarter of 2019, which measures its weakest performance in over five years.

Secondly, Donald Trump’s recent threats to start imposing tariffs on the bloc once he is done with China is putting an additional pressure on the Commission to find new political leverages and partners to counter the hampering influence of American protectionism. There are known parallels between Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, both of whom as populist leaders appear to be quite fond of each other, and should the Commission fail to appease Johnson on time, he might distance the UK further away from the EU and partner up with Trump. Such a development of the situation would undoubtedly worsen the situation for the bloc.

Overall, failing to allow Britain to leave on its own terms might ultimately turn out to stir more divisiveness in mainland Europe than what the Commission presently fears could go wrong with the Irish border. Any indecisiveness on the part of the Commission might cause even more problems in the long-term if Britain and the bloc do not protect their partnership. Finally, we are yet to see whether Johnson's big gamble would eventually pay off, or if it would lead to a worse-off end result for everybody involved.