Power politics is never simple in totalitarian states. Even though many would-be autocrats would love to have their wills imposed upon the misfortunate subjects of such a state, few have the audacity to challenge the supremacy of the 'Dear Leader'.

We do not know whether Kim Jong-Un, the third and arguably most inspired Kim to rule North Korea, is alive at present. It is secrecy that is the mainstay of the Hermit Kingdom's political framework, and its totalitarian regime revolves around the intentional obstruction of information. So even if Kim the third is dead, such information would not likely be made public knowledge right away.

Yet a myriad of speculations have already flooded western media concerning who would be the most likely successor to 'the throne', some even going as far as to speculate about how this would change North Korea's foreign policy towards the west. While North Korea's self-inflicted isolationism is a good way to keep the coronavirus at bay, conjectures about Kim's health are bound to be imprecise, given the level of uncertainty in the country.

What so many political commentators seem to disregard so frivolously, however, is the question of power aspirations, and if anyone would dare to take Kim's position, which is an issue that should not be overlooked. Totalitarianism built around the persona of a single leader is all about that image of the firm and dominant leader, and therein lies the problem. Such totalitarian states oftentimes lack the necessary policies of succession put in place, in case that something were to happen to the larger-than-life dictator, lest that jeopardises the leader's stoic image ante mortem. It is easy to imagine the type of anarchy that might ensue when the otherwise infallible Dear Leader does something as unexpected and uninspired as dying.

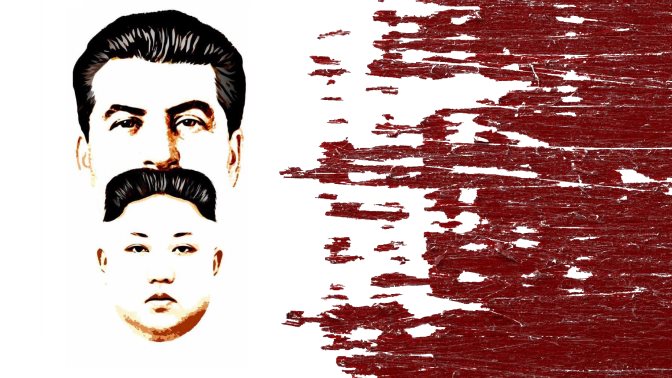

In the relatively early days of Operation Barbarossa –the Nazi plan to occupy the USSR during the Second World War – at one point the Germans reached the gates of Moscow, and almost everything seemed lost for Stalin and his regime. Even when the man of steel himself was at his weakest, no one dared to oppose him. Not even a whimper of discontent, let alone plans for a military coup, were raised against the man who allowed his ideological enemy to reach his doorstep virtually unopposed. Historians now know in hindsight that Stalin was petrified of coup d'état at that time, but apparently, his cronies were even more immobilised by fear than he was, even as the 'throne' was up there for the taking.

The situation now, almost 80 years later, is eerily similar in one of the last remaining strongholds of communism. Even though a global pandemic now replaces the Nazis, the people in Kim's immediate circle face a similar dilemma to the one General Zhukov, and those closest to Stalin faced so many years ago. Do they risk everything when all information is obscured by the long shadow of the totalitarian state, even as the leader appears to be at his weakest, or do they remain watchful? As we have already seen, the consequences of such choices can have profound and long-lasting implications for the world.